Of settlers, colonists and doomers

Note to Substack readers. I replicate the essays that I publish on my chrissmaje.com site here on Substack. I’ve switched comments off here because I don’t want to juggle two parallel conversation threads, but if you’d like to discuss my essays feel free to join the conversation over on my website. Currently, all my content is free, but if you’d care to support my writing by becoming a paid subscriber on Substack, I’d be super appreciative!

A few brief announcements before I launch into a hopefully relevant one-post digression from my present theme of exploring my book Saying NO to a Farm-Free Future.

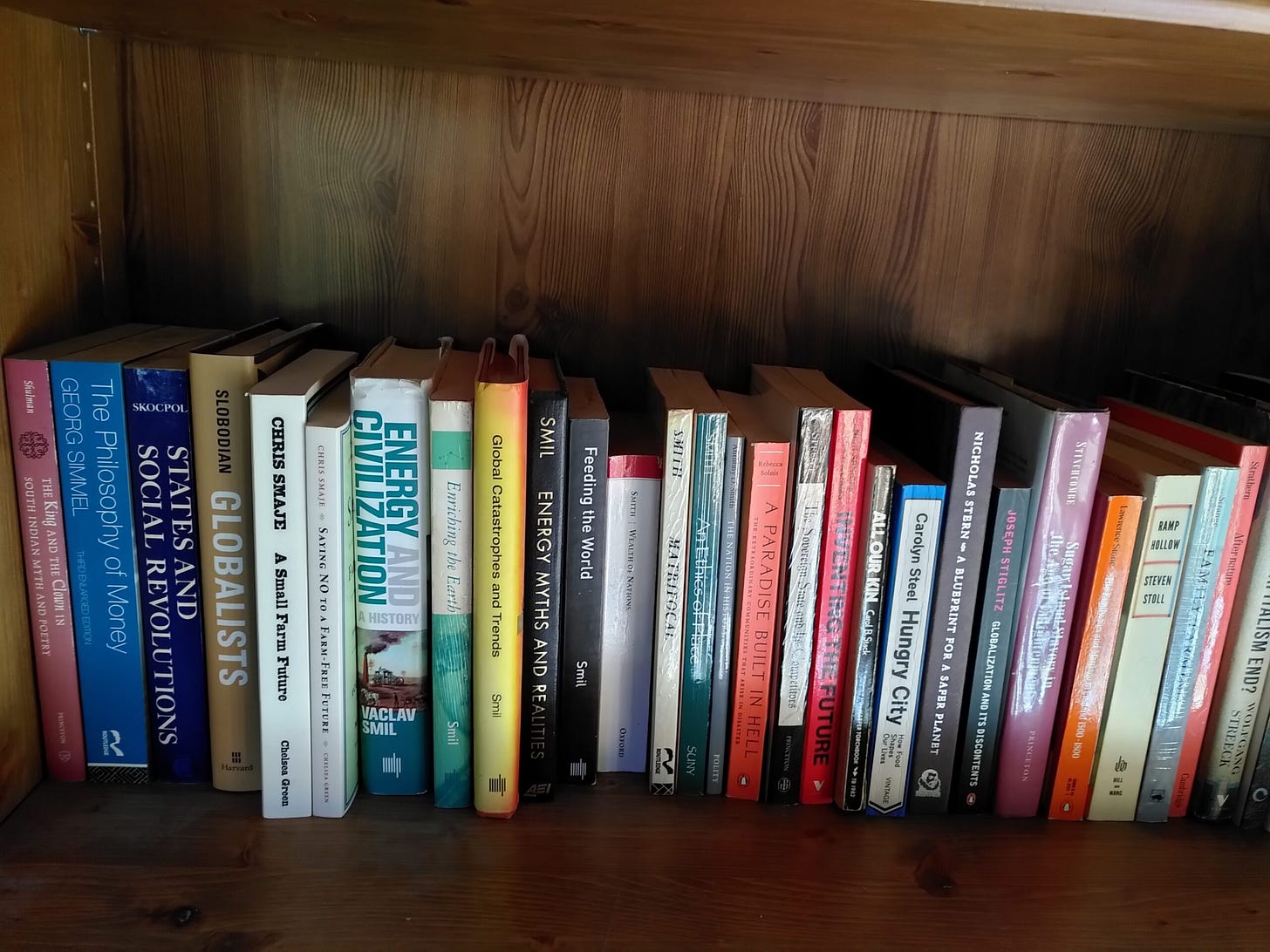

First, Christmas has come early to readers of this blog, with my publishers offering a 25% discount until 1 January on my two books. Frankly, I’d be disappointed if anyone reading this doesn’t already have them prominently displayed on their shelves. But I’ll never know the truth of it, so for the laggards among you, just click here or here and use the code SayingNo25 to claim your reward. This offer, incidentally, applies only in the UK. In the US, Chelsea Green are offering a 35% discount on all books from 20/11 to 15/1 (or 11/20 to 1/15, in the local argot). More evidence, if it were needed, of an over-bless’d country.

Second, The Ecologist has published this short response from me to George Monbiot’s ‘Cruel fantasies…’ piece that they replicated. I’ve published a slightly longer original-draft version of this piece (with references) here, which I’d suggest is the more authoritative version of the article. Getting that piece published has been a tangled tale, but anyway there it now is.

You might also be interested in Million Belay’s article on ‘Africa’s forgotten farmers’ which touches on the debate. And also an article in Civil Eats by Nhatt Nichols, based on an interview she did with me about Saying NO… This page on my website provides a full briefing on the post-publication adventures of my book.

And so on to the main theme of this post, involving a brief retrospective on two podcasts and one book.

The first of the podcasts is #6 of Nate Hagens’ ‘Reality Roundtable’ conversations on his Great Simplification site. The episode featured Jason Bradford, Andrew Millison, Vandana Shiva and Daniel Zetah talking about fossil free food systems. It’s well worth a listen. It covered a lot of similar ground to the discussions on this blog and in my books, although as ever I learned new things from it.

Still, here I want to emphasize the areas of overlap with some of the themes in my recent writing. On the podcast, these included the analogy between cities and livestock feedlots (high efficiency can come at an unpayable cost), a critique of subsidized US commodity export agriculture (low food prices don’t necessarily benefit the poor, or local agroecological farming systems), and a (perhaps overly tentative?) discussion of likely future migration and agricultural patterns as climate, energy, water and other realities change.

It was good to hear other people raising these issues in view of the fierce pushback that’s come my way as a result of saying much the same things. I think we need to lean into these discussions rather than insisting that the high energy urbanizing status quo is non-negotiable and can be sustained by improbable ecomodernist techno-fixes. Which is where I believe articles like Million Belay’s are important, with their message that the best workarounds to the problems faced, for example, by African farmers are likely to be devised by … African farmers. Still, Nate’s roundtable discussion raises some further questions here that I’ll come to in a moment.

One further point about the roundtable. The issue arose of terraforming to create livelihood resilience – in this instance, detailed, small-scale terraforming at the household, farmstead or local community level, the kind of labour-intensive thing that permaculture design tends to emphasize. You can do it in urban and suburban situations to some degree, but you can also do it in rural ones. In the latter case, you probably need more people occupying rural space than is typical in most European or North American farmscapes today.

The second of the podcasts was Jason Snyder’s Doomer Optimist interview with historian Steven Stoll, whose book Ramp Hollow I’ve enthused about before – a history of land use and land title in Appalachia (it’s more interesting than it sounds, okay…) with much wider implications.

There’s a ton of things I’d like to say about this interview, but for now I’ll restrict myself to three. First, it’s worth listening carefully to what Stoll says about common and private property and the nature of capitalism. People on both the political left and right get into real tangles on these issues, and Stoll lays out the issues very well. From a left perspective, it underscores points I’ve often made here: common property isn’t necessarily positive and progressive, while private property isn’t necessarily the horror show it’s often made out to be. Context is everything.

Second, talking of left and right, Stoll negotiates the shifting political territory around this in interesting ways in the podcast. As I see it, too much left-wing analysis these days buys into top-down techno-fixes barely distinguishable from corporate greenwash, except for a largely gestural hatred of the Tories or whoever, and an insistence that it’s all, like, for the people. And too much of the remaining left-wing analysis that doesn’t make this mistake is in hock to problematic ideas of state collectivism. So I like Stoll’s basically distributist notions of farmstead-owning collectivism. Likewise his criticisms of the ‘capitalism as freedom’ school of thought on the political right, which fails to recognize the extent to which contemporary capitalism is simply another form of state collectivism.

Which brings us to the third point – markets. Stoll rightly points out that markets are the small farmer’s friend, as long as the farmer retains access to non-market sustenance. This is terrain I covered in Chapter 14 of A Small Farm Future, partly with reference to Adam Smith’s distinction essentially between commercial societies built on local agricultural development and capitalist societies built on maximizing returns to capital through colonialism and global trade.

Stoll is one of several influences recently making me wonder if I’ve over-emphasized agrarian autonomy and self-reliance in my writing. I think it’s necessary as a defence against the over-commodification of capitalist trade, but I do think trading food and fibre locally is an important part of a congenial small farm society.

Where such arrangements have worked historically, it’s usually either been via enlightened top-down governance that ensures usury and fiscal abstraction don’t get out of control, or via bottom-up local moral economies able to avoid the extractions and abstractions of more powerful economic players. The trouble is, I can’t really foresee how either of those would easily take root in the near future most of us face, involving decaying capitalist nation states along with a lot of migratory money and people. Much as I want to emphasize the virtues of the local, in the future the local is going to have to be forged anew – and quickly – by people who weren’t necessarily local to begin with. I think that’s going to be pretty difficult and I don’t have great answers as to how to make it easier.

But I do have some answers nonetheless, which I hope to discuss in more detail soon. The answers in brief revolve around people quickly reconstituting themselves as peasantries, with local moral economies and agrarian populist politics, as discussed in Chapters 19 and 20 of A Small Farm Future.

One thinker I’ve found useful in getting to grips with this is the late Christopher Lasch, notably in his book The True and Only Heaven: Progress and its Critics (1991). Recently, I came across an interesting critical essay about Lasch by Rich Yeselson (the essay itself is not recent, but I’ve never been overly concerned about newness or being on-trend). I agree with some of Yeselson’s criticisms, even while finding his position generally a bit too complacently liberal-modernist. But where I mostly disagree is in his objections to Lasch’s fixation with the populist politics of artisans, small farmers and proprietors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The problem with this for Yeselson is that “all of these people are dead”, so “they are inadequate agents to carry forward a critique of modernity”. But as I see it, their ideas (or at least the ideas that Lasch invested in them) are not dead. They’re very much waiting in the wings. Our task today is to bring them centre stage.

Anyway, enough on that for now. Finally, a few words on the book I mentioned – namely Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse. The book is a wonderfully thought-provoking meditation on climate change, geopolitics and colonialism, written by someone who – praise be! – understands that quantification is an important intellectual practice, but also an ideological one that can envelop an issue in an obscuring ‘fog of numbers’, to coin one of Ghosh’s chapter titles. I don’t think this is an especially hard issue to grasp, but it seems quite beyond some people nowadays.

Again, there’s a ton of things I’d like to say about Ghosh’s book, but I’ll stick with just one (okay, two – I’m also going to mention briefly Ghosh’s very interesting discussion of settler-colonial terraforming. To be compared and contrasted with the kind of localist, permaculture-inspired terraforming discussed on Nate’s show).

But my main point relates to a debate here a while back about climate ‘doomism’, which some commenters saw essentially as a self-indulgent affectation of, shall we say, ‘well fed’ people in the Global North. I felt at the time that this was a wrongheaded criticism, and I find support for that in Ghosh’s book.

‘Doomism’ is one of those pejorative terms that gets repurposed positively by those it seeks to ridicule. I guess I’m a doomer in the sense that I don’t see any dominant technological or political trend in modernist global society that’s going to rescue it from biophysical and socioeconomic disorder. Which is not at all the same thing as welcoming that disorder in the hope it will result in the kind of society I’d like to see, or surrendering politically to whatever happens (Eliot Jacobson has written a nice little essay touching on this ).

In Chapter 13 of his book, Ghosh describes the sense of racial privilege attending climate change narratives in the Global North. It has two faces – the anticolonial argument that the suffering is disproportionately concentrated among poorer and darker-skinned people in the Global South, and the neocolonial argument that this concentration reflects the weakness and inferiority of these people and/or their countries. The first of these faces isn’t unreasonable and I can sign up to it myself to some degree, but I think it does implicitly recuperate a sense of the superiority of the Global North, just as the second one does … a superiority that lurks within ecomodernist plans to save the world through bacterial protein, nuclear energy and so on, and a superiority that invests all those tiresome indictments of low-energy localism for its bucolic romanticism or whatever.

Ghosh isn’t convinced the cards will fall quite so one-sidedly to the benefit of the Global North this time around. Neither am I. The implications are huge and I won’t discuss them here. But while I don’t welcome the chaos that’s unleashing, I can’t honestly mourn the passing of a modernism that was always rotten to the core and that always had doom written into it. It’s vital now to wrest the best outcomes we can from its passing. In my opinion, this won’t be achieved by ‘we can do this’ techno-narratives built around ongoing processes of capital accumulation in the Global North, nor by derision towards lower energy and more local ways of being.

Ghosh says, rightly I think, that “the settler-colonial holocaust that has devoured so many Native American life-worlds will one day engulf the entirety of the planet” (p.207). But while that holocaust destroyed many people, along with their life-worlds, it didn’t destroy all of them, nor all of the world. The challenge then is to do what we can now to start reconstructing better life-worlds that can hopefully come to fruition once the fire of the settler-colonial world-holocaust has burned out.

Perhaps there’s an irony here in my juxtaposition of Lasch and Ghosh as influences, since you could interpret Lasch’s position (albeit rather unfairly in my opinion) as a justification for settler-colonialism. Here’s how I’d parse it: being a settler is going to be an increasingly common human experience in the future. Lasch teaches us useful things about the politics of settler livelihood-making, while Ghosh teaches us useful things about how settlers must avoid becoming settler-colonists.